See more: Is Nicole Shanahan the Most Dangerous Woman in America?

The ex-wife of Google’s Sergey Brin poured divorce money into Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s campaign and became his running mate, with potentially cataclysmic consequences.

When Google co-founder Sergey Brin began openly dating Nicole Shanahan, in 2015, some members of his circle assumed it was a fling. Fresh out of law school, she was 12 years his junior, with few of the qualifications that might level the power dynamic with the world’s seventh-richest man. “I thought, OK, she’s fine,” a person close to the situation told The Daily Beast. “And then it went on.”

By the time they married, in 2018, Shanahan had slingshotted into Silicon Valley stardom. She socialized with other billionaires’ plus-ones, distributed millions to pet causes—sometimes igniting controversy—and worked to distance Brin from his ex-wife, 23andMe co-founder Anne Wojcicki, who had remained close with the billionaire, according to multiple sources with knowledge of the relationships.

But almost as quickly, Shanahan’s marriage to Brin deteriorated. The couple squabbled over the right approach to raising their daughter, who was diagnosed with autism, and Shanahan chafed at Brin’s left-brain thinking. There was also the matter of her alleged affair with Elon Musk in 2021, a betrayal so profound and astonishing that the starchy pages of The Wall Street Journal might briefly have been confused for a tabloid.

Over the past year—armed with a mountain of divorce-settlement cash—Shanahan has found a new ally in Robert F. Kennedy Jr., the black sheep of America’s most famous political dynasty, whose conspiratorial predilections have disturbed many scientific minds in Silicon Valley and often made the candidate a spectacle. (He has also made headlines for other reasons. This week, in an unexpected twist, it was revealed that he once claimed to be suffering from memory loss because a worm had crawled into his skull, eaten some of his tissue, and then died.)

Shanahan’s relationship with Kennedy leveled up earlier this year, when her new romantic partner, Jacob Strumwasser, a Bitcoin enthusiast whom she met, naturally, at Burning Man, suggested to Kennedy that he consider Shanahan as his vice presidential nominee. Kennedy bit, and Shanahan soon assumed an even larger platform, where she wasted no time mirroring his contrarianism, warning about unproven health risks associated with “electromagnetic pollution” and railing against certain COVID vaccines.

On a podcast this month, she echoed conservative talking points, arguing that almost all women contemplating an abortion would choose to give birth if they were given enough resources. She also stated, without providing evidence, that demonstrations in support of Gaza on college campuses are being fueled by paid protesters.

“I don’t know how these things happen. It’s a crazy story.”

Interviews with 10 people who have been close to Shanahan, and several others in her orbit, reveal two deeply polarized camps. Her acolytes see the consummate American success story: the child of impoverished parents who battled her way to prosperity.

“Smart, honest, diligent, strategic and tenacious do not begin to capture her essence,” said Erich Spangenberg, who acquired Shanahan’s intellectual property tech startup in 2020. (He nevertheless plans to vote for Donald Trump.)

The other faction is aghast that Shanahan, in a highly unlikely alternative reality, could be one beating heart away from the presidency—or, more believably, that she and Kennedy will help tilt the election to Donald Trump, as some polls have shown they will do.

“I look at her and I’m like, I don’t know how these things happen,” said a person who has spent significant time with her. “It’s a crazy story.”

The Kennedy campaign did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

In a race that might come down to tiny margins, Shanahan, an unknown figure to most Americans, could determine the most consequential election in generations. Twenty-four years ago, Green Party candidate Ralph Nader helped deliver George W. Bush the presidency by winning 97,000 votes in Florida—a state ultimately decided by fewer than 1,000 ballots. Four elections later, in 2016, fellow Green Party nominee Jill Stein was accused of knifing Democrats once more, this time by drawing votes from Hillary Clinton in her run against Trump.

Neither of those candidates had Kennedy’s name recognition, nor Shanahan’s near-limitless war chest. Armed with her cash, Kennedy says he has already gathered enough signatures to appear on the ballot in three swing states, with more to come, and has formed an eclectic coalition of supporters, from disgraced actor Kevin Spacey to billionaire Bill Ackman, venture capitalist David Sacks, Trump megadonor Timothy Mellon, and podcaster-in-chief Joe Rogan. He is averaging 10 percent support in national polls, according to FiveThirtyEight.

Even some of the people who know Shanahan best are bewildered by her newfound power.

“Other than the fact that she has a bunch of money, I don’t know why anyone would vote for her to run anything,” said one of her detractors. “And I don’t just mean vice president.”

Shanahan grew up in Oakland, California, in a brutally turbulent home. Her mother immigrated from Guangzhou, China, in 1983. Her father, the son of two professional figure skaters, was an alcoholic with manic depression. Her parents had a difficult marriage, but the family lived together.

“We didn’t have money to live in separate homes, even though I think it probably would have been safer,” Shanahan explained on a podcast this month with former ESPN personality Sage Steele. When she was around 10 years old, her father’s mental health worsened; he “became a hermit” and rarely left their house. At 12, Shanahan started bussing tables.

“My only way out was going to be college,” she recalled on the podcast—a friendly interview in which Steele sat cross-legged and neither woman wore shoes. She selected the University of Puget Sound, a small school with a verdant campus in Tacoma. Her two main criteria: the university’s acclaimed arboretum—”I love trees”—and its study abroad program. Shanahan didn’t have the funds to visit campus before enrolling, she said, but she had earned a merit scholarship. She chose to concentrate in economics, Asian Studies, and Mandarin.

According to her biography on the Kennedy campaign website, Shanahan ran varsity cross-country at Puget Sound, though several members of the team contacted by The Daily Beast did not remember her. “She could have been on the team, but it’s not something that sticks out in my mind,” said Mike Orechia, who coached the squad during her tenure.

Orechia later followed up to say that he had pulled up Shanahan in his files. She was on the roster for a fleeting moment her freshman year. She ran just the first three races of the season, finishing outside the top-ten in all of them, then withdrew from the team.

Years earlier, as a preteen, Shanahan had somewhat idiosyncratically decided that she would grow up to specialize in intellectual property law, and during college she sought mentorship in the field.

“I just went on the internet and wrote letters to every single patent attorney in Seattle” and offered to work for free, she recounted to Steele. At night, she said, she waited tables at a sushi restaurant.

Pete Thompson, a photographer who met Shanahan around the time of her college graduation, described her as friendly and palpably ambitious, though it wasn’t clear to him how she would channel her drive. She dabbled as an “aspiring model,” he told The Daily Beast, and they did a “little shoot,” but the pictures never made it to print.

“I think if you knew her at that time, you would definitely get the sense that her ambition sort of eclipsed being liked,” he said. “It was very much like, OK, I’m going to do something big.”

Life after graduation wasn’t immediately glamorous. Shanahan worked a series of sleepy intellectual property jobs before enrolling at Santa Clara University School of Law in 2011, at the behest of her aunt. Around the same time, she founded her startup, ClearAccessIP, which helped companies organize their patent portfolios.

Shanahan listed her boyfriend, tech investor Jeremy Kranz, as one of the company’s early contributors—though it wasn’t apparent if he actually held a formal role. Kranz would later become her first husband. The pair got engaged in 2013, and Shanahan converted to Judaism; that December, portentously, she attended the Breakthrough Prize scientific awards ceremony in Silicon Valley, as she documented in an awed Instagram post at the time. The first presenter listed on the program was a billionaire cofounder of the prizes: Sergey Brin.

The next summer, Shanahan and Kranz were scheduled to get married. Weeks before the ceremony, she attended a yoga retreat in Lake Tahoe for her bachelorette party, where she met Brin in person, said a person with knowledge of the situation. She allegedly began an affair with the billionaire, and after the wedding Kranz stumbled upon the alleged infidelity.

“Why is my wife getting a text from Sergey Brin?” he questioned, according to a person familiar with his thinking. As the Daily Mail reported last month, Kranz filed to nullify their marriage after just 27 days, on the basis of unspecified “fraud.” He later agreed to a more simple dissolution. Shanahan waived alimony but got to keep her Toyota Prius and a Yorkshire terrier. (Kranz did not respond to a request for comment on Wednesday.)

As a child, Shanahan told Sage Steele this month, her “dream was to have a peaceful home.” But even hitched to one of the world’s wealthiest men, the fantasy proved elusive. Brin had separated from Wojcicki in 2013, after having an affair with a female Google executive. The former couple remained on cordial terms, however, according to multiple people with knowledge of their relationship.

Brin and Wojcicki didn’t implement a rigid custody system for their two children. They lived near each other, and the kids “would come and go” as they pleased, a person close to the situation recalled. “Nicole disrupted all that” and pushed for stricter rules, the person said. Her relationship with Wojcicki grew fraught. (Wojcicki declined to comment.)

Brin was consumed by his own career and interests, and therefore had no qualms about Shanahan’s more dubious beliefs, another person familiar with his thinking said. In 2018, they had a daughter, Echo, who was later diagnosed with autism. Shanahan told Steele that motherhood changed her life. “Through [Echo’s] experience, I’ve seen everything differently,” she said.

To some observers close to her, the autism diagnosis accelerated Shanahan’s attraction to unproven scientific theories, and later her alignment with Kennedy.

In the speech announcing her candidacy in March—delivered in a languid tone that contrasted with Kennedy’s harsh intensity—Shanahan said she “got deep into the research” after Echo was born and came to believe that autism and chronic diseases are mainly caused by medications, electromagnetic pollution, and “toxic substances in our environment.”

“She’s always been a crystal gazer,” a person who has spent considerable time with her said. But Echo’s struggles pushed her deeper into the fringes. “People who have children [in that position], their views can sometimes be swayed, because you’re looking for an answer that doesn’t exist.”

In 2019, aided by a gift of more than $23 million in shares of Google’s parent company, Alphabet—courtesy of Brin—Shanahan launched a nonprofit called the Bia-Echo Foundation, with a focus on reproductive health, criminal justice reform, and environmental causes. She named Chloe Cockburn—a philanthropic adviser, the sister of actress Olivia Wilde, and the daughter of a dynasty of left-leaning journalists—as a director.

Shanahan also poured millions of dollars into the Buck Institute for Research on Aging to establish a center devoted to female reproductive longevity, with the goal of delaying or eliminating ovarian aging. The issue was personal to Shanahan, who was once told she was not a good candidate for IVF due to polycystic ovarian syndrome, she said in a 2023 interview with The New Yorker.

Two people familiar with Shanahan’s donations said she caused discord by attempting to intervene in the Buck Institute’s work. She allegedly sought to block at least one partnership based on personal animosity, one of the people said.

Jennifer Garrison, an assistant professor at the Buck Institute and a member of the center, denied that Shanahan has meddled in its operations. “She’s definitely, you know, not part of our day to day,” she said, adding that Shanahan was “really prescient to understand that this was going to become an important topic, and I’m grateful that they gave us the capital to start this.”

A spokesperson for the Buck Institute also disputed that she has played a role in “strategy, partnerships, or scientific direction.”

As her philanthropic reputation blossomed, Shanahan’s marriage began to falter. The couple had different views on how to care for their daughter—a dispute that continues to present day. Outwardly, they were also very different people.

“At the end of the day, he’s an engineer” and is often inclined to “come from a more analytical perspective than an emotional one,” said Shruti Ganguly, a filmmaker close to Shanahan, though she cautioned that she was not privy to the details of their marriage. (Ganguly added that Shanahan, who is producing a film with her on civil rights activist Shirley Sherrod, also has analytical skills.)

Those are the family-friendly explanations. As The Wall Street Journal previously described in stunning detail, in 2021, Shanahan engaged in a “brief affair” with Elon Musk—one of Brin’s close friends—at the Art Basel festival in Miami. It was an act of disloyalty befitting a soap opera, and it left Brin gutted, said a person familiar with his reaction. Musk allegedly kneeled before Brin at a party to apologize, but the mea culpa didn’t seem to take: The billionaire filed for divorce from Shanahan in January 2022 and allegedly “ordered his financial advisers to sell his personal investments” in Musk’s companies. (Both Musk and Shanahan have strongly denied any romantic involvement.)

Brin and Shanahan had a prenuptial agreement, but she argued that she had assented to it under duress, since she was pregnant with Echo, the Journal wrote. She reportedly sought a settlement worth over $1 billion.

“I think it was probably a lot easier for him to just shell out. While it’s crazy money to humanity, it isn’t to him.”

Rather than litigate, Brin paid a large sum to end the marriage. In May 2023, roughly two weeks before a judge finalized their divorce, he gifted more than 5.2 million shares of Alphabet to an unnamed entity, according to public filings; today, those shares are worth more than $800 million. Brin has not given away any stock since.

Neither he nor Shanahan have commented on the settlement, but the transfer had the markings of a divorce payment. Daniel Jaffe, founding partner of Jaffe Law Group in Los Angeles, said Brin would have incurred a far higher tax burden if he had given cash to Shanahan rather than stock, and the timing of the transaction makes sense; if the parties had already come to an agreement, the judge’s approval two weeks later was essentially a formality, and there would be no reason to delay making the transfer. (Google did not respond to requests for comment.)

“I think it was probably a lot easier for him to just shell out,” a source familiar with Brin’s thinking said. “While it’s crazy money to humanity, it isn’t to him.”

Shanahan’s startup, ClearAccessIP, hobbled along before fizzling, too. She launched the firm in 2012, California business records show, and raised millions of dollars promising an AI-powered platform that would facilitate patent applications. Ironically, when she sought to patent ClearAccessIP’s signature technology in 2017, the patent office slapped her down.

Shanahan tried several more times to win proprietary rights for the company’s software, fighting through a multi-year appeals and reapplication process, to no avail. Despite her own credentials as an intellectual property attorney, she brought in two successive law firms after failing pro se, only for them to come up short, too. The most recent rejection arrived last September.

“She’s really trying. She’s really trying hard. But she just can’t do it,” patent attorney Russ Weinzimmer told The Daily Beast.

Weinzimmer also noted that when Shanahan first applied for a patent, she signed documents attesting that the company qualified for fee discounts as a “micro-entity,” meaning that neither she nor any party with ownership interest in the invention had earned more than $169,548 the prior year. The discounts likely amounted to only a few hundred dollars, he said—which surprised him, given her then husband’s staggering wealth.

Brin was at least lightly involved in the business, said Dylan Gittleman, a ClearAccessIP adviser. “He’d come by, he’d provide input. And, you know, some of us thought maybe down the road Google would acquire the entity,” he said.

No such luck. Instead, in 2020, Shanahan offloaded the company to a firm called IPwe for a mix of cash and stock, said Spangenberg, IPwe’s founder.

“The company was sold owing to multiple circumstances that included that she had a baby… And then the marriage was going south, and she just didn’t have the time to commit anymore,” added Gittleman, who spoke highly of Shanahan.

He described the deal as a “pretty successful” exit, though the cash portion of the transaction was likely small, since IPwe had raised just $5 million at the time of the acquisition, according to PitchBook.

The combined companies struggled to maintain traction. In March, IPwe filed for Chapter 7 liquidation. Its bankruptcy petition revealed that it had just $50.54 in its bank account. The total value of all its intellectual property holdings in the most recent tax year was just $2,394.

Earlier this year, Shanahan and her new partner were at dinner with Kennedy and his wife, Cheryl Hines—who starred on Curb Your Enthusiasm—when Strumwasser made his proposal for Shanahan to enter the veepstakes.

“Both Cheryl and Bobby spin around in their chairs, and they’re looking at me, and they’re like, ‘Would you consider it?’” Shanahan recounted on Steele’s podcast.

“I said, ‘Well, no one’s asked me.’”

Soon after, Kennedy informed Shanahan that she was his pick. In public, he forcefully denied that he would ever “choose a vice presidential candidate based on how much money that they have.” But it was hard to dispute that his campaign was thirsting for cash, and that Shanahan had already ponied up $4 million to help pay for his Super PAC’s controversial Super Bowl ad in February, which mirrored a famous advertisement once run by John F. Kennedy.

Shanahan touted her credentials, including her work at the Stanford Center for Legal Informatics, where she conducted research “on the pace and nature of society’s adoption of artificial intelligence for law and government,” according to her academic profile.

“I’ve been, you know, standing in line at Safeway with food stamps. And I’ve been flying all over the world in helicopters and private planes,”

— Nicole Shanahan

She also argued that her disparate life experiences make her a uniquely qualified running mate. “I’ve been, you know, standing in line at Safeway with food stamps. And I’ve been flying all over the world in helicopters and private planes,” she told Steele.

Shanahan’s campaign biography paints her as an approachable nature lover—matching Kennedy’s branding—and notes that she surfs and snowboards, owns two dogs, and grows her own food with Strumwasser.

Asked in an interview with NewsNation why Shanahan would be qualified to run the country, Kennedy described her as an “expert” in artificial intelligence and chronic diseases. “People have said to me, ‘Well you should’ve brought an insider in as VP. No, the insiders [are] the ones who gave us the chronic disease epidemic.”

Kennedy’s pitch does not square with some close-range perceptions of Shanahan. A person who knows her well dismissed the notion that she has cutting-edge expertise in artificial intelligence, asserting, a little hyperbolically, that she couldn’t differentiate “AI from a tennis ball.”

Peter Hotez, professor of pediatrics and molecular virology at Baylor College of Medicine, was also incredulous. “No physician scientist that I know of would ever claim that they’re an expert on the entire category of chronic illness. That’s absurd,” he said. “And the idea that someone like Nicole Shanahan, who has no formal training in medicine or science, appoints herself an expert is just ridiculous.”

Numerous members of the Kennedy dynasty have publicly rebuked RFK Jr.’s candidacy. Over the summer, after he argued that the coronavirus may have been “ethnically targeted,” his brother Joe Kennedy II called his statements “morally and factually wrong.”

Months later, when RFK Jr. ditched the Democratic Party and vowed to take on Joe Biden as an independent, four of his siblings released a statement blasting his “dangerous” campaign. “Bobby might share the same name as our father, but he does not share the same values, vision, or judgment,” they wrote.

Among Biden supporters in Silicon Valley, Shanahan has been accused of a similar betrayal.

“In the past I would’ve described her as a conventional liberal—very, very upset when Hillary lost to Donald Trump,” said one of her former social contacts. “But she wouldn’t be the first politician, and I put that in quotes, who changed her position to suit her needs.”

Kennedy has rejected calls to drop out of the race and denies that he will sink Biden’s chances. Last month, he joyfully declared himself a spoiler candidate both “for President Biden and for President Trump.”

Weeks since her premiere on the ticket, Shanahan is still taking things slow. A Washington Poststory on May 4 noted that she had not attended a single in-person campaign event and has remained an enigma even to Kennedy’s own supporters.

There are still six months to the election, plenty of time for anything to change. But Trump and Biden’s team are already flaming Kennedy, and the catastrophizers who have spent time with Shanahan are panicked that her money might seal the demise of the American experiment, even if Kennedy bombs at the ballot box.

“Brin invented Google”—once heralded for its “Do No Evil” slogan—“and you’d think that would always be the thing he would be most famous for,” a person close to the billionaire said. “But if his divorce money ends up destroying democracy by re-electing Donald Trump, I think that will trump the story.”

The truth is that Shanahan has little to lose. Born into nothing, she slowly laddered up: scholar student, college graduate, lawyer, wife, philanthropist, near-billionaire divorcee. And the oxygen, where she stands, is apparently still not sufficiently thin.

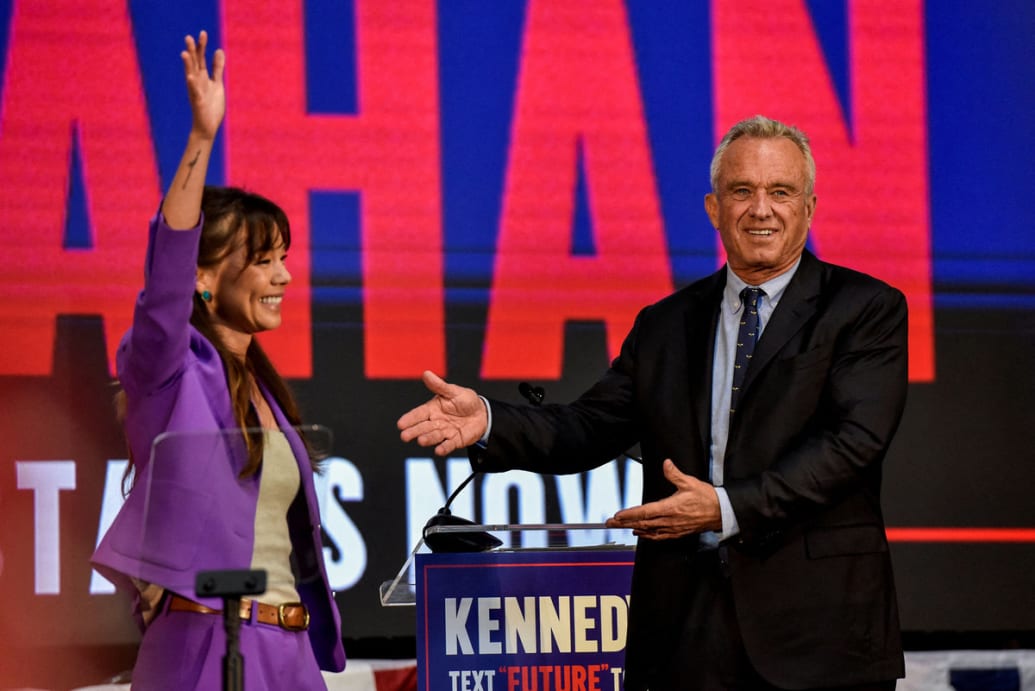

At her campaign announcement in late March, Shanahan stood before Kennedy’s rowdy fans, beamed in her lilac pantsuit, and made a brash prediction: “I will be the youngest vice president in American history.”